Idaho, Nevada (USA)

- 28. Feb. 2019

- 5 Min. Lesezeit

Aktualisiert: 1. Feb. 2021

Since the late 2000s, palaeontologists of the University of Zurich, in collaboration with US colleagues, conducted field campaigns in the Western United States (Idaho, Nevada), with the aim of finding Early Triassic fish fossils. The material collected during these fieldwork seasons is in part published and in part currently under study.

Bear Lake County, Idaho

Early Triassic fishes from Bear Lake County, southeast Idaho, are known since the early 20th century, but only a handful of studies focussed on them up to today. Fossil fishes of Early Triassic age can be found in several localities in Bear Lake County (and neighbouring areas) and are derived from different levels and formations. During our 2009 and 2013 fielwork seasons, we mainly concentrated on a locality west of Georgetown, where outcrops of the late Smithian (early Olenekian, Early Triassic) Anasibirites ammonoid beds are accesible (Photo below: steep bluff west of Georgetown). The fossils are preserved in calcareous concretions in the rock layers, and can thus be dated accurately.

The Anasibirites beds near Georgetown have yielded, among others, a few nicely preserved skulls of the ambush predatory ray-finned fish Saurichthys, one of which was published in 2012 in Bulletin of Geosciences (open access).

The published Saurichthys material from the Georgetown locality is preserved in 3D. At the time of its discovery, it represented the only occurrence of this genus in the USA (material of Saurichthys was later also discovered in Nevada, see below). In our 2012 paper, we discuss the geographic and stratigraphic distribution of this genus, which has been recovered from Triassic deposits around the world. We found that Saurichthys had a cosmoplitan distribution during the Early Triassic, occuring both in marine and freshwater environments. Later in the Triassic, its distribution was more geographically restricted. Species diversity was likewise highest during the Early and Middle Triassic but distinctly lower during the Late Triassic. We also investigated morphological changes within Saurichthys during the Triassic and found that many Early Triassic species differ from their Middle and Late Triassic relatives, most strikingly in their more extensive scale cover. Below are a life reconstruction of the Triassic fish Saurichthys (from Kogan & Romano 2016), and a photo of the first Georgetown skull discovered during the 2009 expedition, which we describe in our paper.

This particular skull unfortunately could not be used to study the internal skull anatomy using μCT (X-ray microtomography). However, other Saurichthys skulls from the Early Triassic of Greenland and Nepal proved to be highly useful for such studies, and helped to better understand the relationships of Saurichthys to other fishes (see our open access paper).

More recently, a new, diverse fossil assemblage has recently been discovered in Paris Canyon, west of Paris (Bear Lake County, Idaho, USA). This new biota comprises fossils belonging to several phyla, including vertebrates (e.g. chondrichthyan and osteichthyan remains). It is thus one of the earliest diverse assemblage after the end-Permian mass extinction event. An overview of this early Spathian aged assemblage, coined the "Paris Biota", was published in the journal Science Advances (open access). The following figure shows an artist's depiction (credits: Jorge A. Gonzalez) of the Paris Biota, including all groups that were found. Note that bone fossils from the Paris Biota were only found for fishes, whereas the presence of other vetrebrates is evidenced by coprolites (fossilized feces). Marine reptile fossils (bones) are known from other sites in Idaho and Wyoming.

A thorough description of the chondrichthyan (shark) fossils from the Paris Biota will soon be published in a special issue in the journal Geobios.

Additional fish fossils recovered from Early Triassic strata in several sites in southeast Idaho are currently under study.

Elko County, Nevada

Unlike Idaho, Early Triassic fishes from Nevada are barely known. A few occurrences have been only casually mentioned in the scientific literature, but until 2017 no descriptions have been published. During several recent expeditions, new material of bony fishes has been collected from Early Triassic aged strata in Elko County, northeast Nevada, and Esmeralda County, south-southwest Nevada (see below).

Fossil ray-finned fishes from Elko County, now published in Journal of Paleontology, have been found in three sites: Winecup Ranch, Palomino Ridge, and Crittenden Springs. Two large skulls belonging to the Triassic predatory actinopterygian Birgeria were found south of the Winecup Ranch. One of them can be referred to a new species, which we named Birgeria americana. Birgeria had a worldwide distribution during the Triassic period (ca. 252-201 million years ago), with the largest species reaching slightly over 2 m body length. Birgeria americana is the earliest large-sized species, reaching a total length of ca.1.80 m. Its size was estimated by comparing the length of the fossil (skull fragment) with that of complete fossils of other species. The following montage shows the fossil of Birgeria americana (bottom right), a life reconstruction of this species (credits: Nadine Bösch) and a size comparison with an adult diver. The fossil shows the part of the "cheek" region located behind the eye (as shown in the figure below). A 3D digital surface scan of the fossil can be viewed at MorphoMuseuM.

In addition, a skull fragment of the ambush predator Saurichthys was found on Palomino Ridge near Currie, described in the same paper. This and other occurrences in Idaho (see above) suggest that Saurichthys was relatively common in the subequatorial sea that covered the western USA during the Early Triassic epoch. The occurrence of Birgeria and Saurichthys near the ancient equator challenges a previous hypothesis that vertebrates were absent at low palaeolatitudes due to hot temperatures.

From Crittenden Springs, a famous ammonoid collecting site, we described an incomplete ray-fin of unkown affinity (probably a ptycholepid) in the same paper. Although this fossil cannot be ascribed to a species, it is of interest because it originates from rock layers of Spathian age (late Olenekian, late Early Triassic). The Spathian is the last stage of the Early Triassic and had a longer duration than the first three stages combined (ca. 3 million years). Nonetheless, only very few bony fish fossils are known from this interval (and the same is true for the subsequent Aegean and Bithynian substages of the Anisian, Middle Triassic). Spathian bony fishes have recently been discovered at several sites in the western USA, and a second fossil was recently found at Crittenden Springs. Further studies on these sites may thus help us filling the "Spathian-Bithynian gap" in the fossil record of bony fishes. I investigated the impact of the Spathian-Bithynian gap on our understanding of the Triassic diversification of bony fishes in an open-access paper.

Esmeralda County, Nevada

In 2008, articulated and often largely complete bony fishes were inadvertently discovered in the Candelaria Hills, a low mountain range situated south of the long-abandoned silver mining boom town of Candelaria (Mineral County, south-southwest Nevada). The fishes were collected from the lower portion of the Candelaria Formation, which is of middle-late Dienerian age (Induan, Early Triassic). An exposure of this formation in the eastern portion of the Candelaria Hills (Esmeralda County) proved to be prolific, yielding many well-preserved bony fish remains. The fishes lived less than a million years after Earth's most devastating mass extinction event at the Permian-Triassic boundary (ca. 252 million years ago). At that time, the layers of the Candelaria Formation developed at the bottom of a warm sea at the west coast of the Pangaea supercontinent, close to the equator.

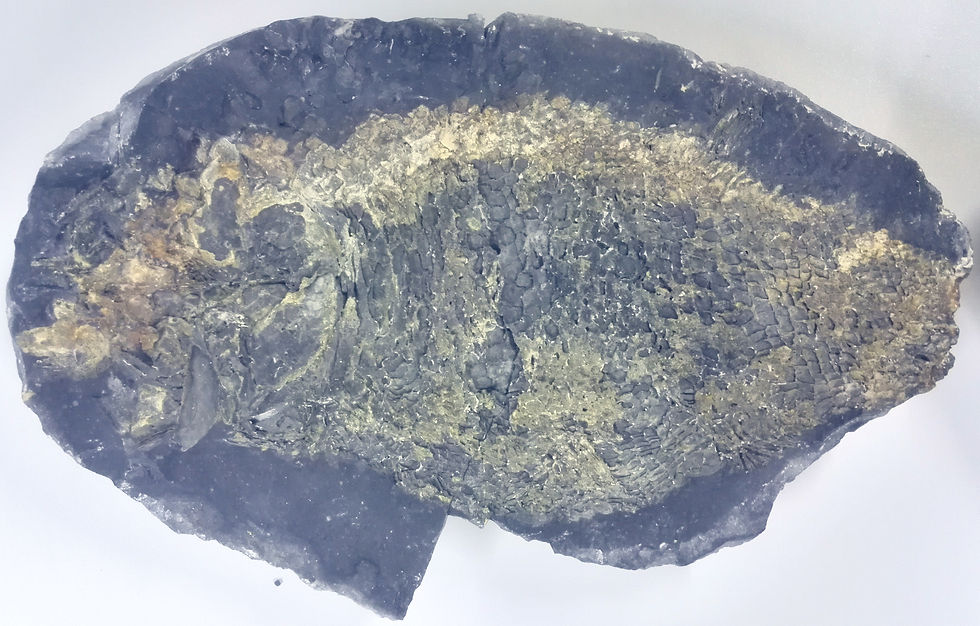

Our study will soon be published in the Journal of Paleontology. We describe three new species of ray-finned fish: the turseoid Pteronisculus nevadanus, the ptycholepid Ardoreosomus occidentalis and the parasemionotid Candelarialepis argentus (photo below), alongside other remains that are not identifiable to species level. The new species belong to families that are known from several other sites around the world, thus confirming their widespread distribution shortly after the mass extinction event. They may suggest similar living conditions.

The majority of the recovered fish fossils from the Candelaria Hills belong to coelacanths. This material is currently under study. Coelacanths used to be more diverse and more common in the past, but are today only represented by two species living off the coast of southeast Africa and Sulawesi island (Indonesia), respectively.

Updated soon.

Kommentare